Three southern resident killer whales declared dead plunging population to 73

VANCOUVER — Three southern resident killer whales have been declared dead by the Center for Whale Research, bringing the population down to 73.

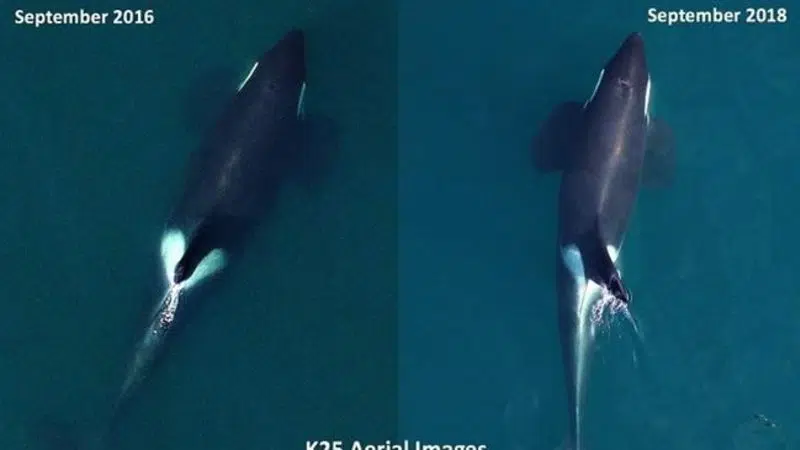

The dead killer whales are a 42-two-year-old matriarch known as J17, a 28-year-old adult called K25, and a 29-year-old male called L84, the institute posted on its website.

“These whales are from the extremely endangered southern resident killer whale population, that historically frequent the Salish Sea almost daily in summer months,” it said.

Experts had expressed fear after two southern resident killer whales, J17 and K25, hadn’t been seen for a few months.