Commons committee urges feds to consider decriminalizing simple drug possession

OTTAWA — The House of Commons health committee is urging the federal government to look at Portugal’s decriminalization of simple possession of illicit drugs and examine how the idea could be “positively applied in Canada.”

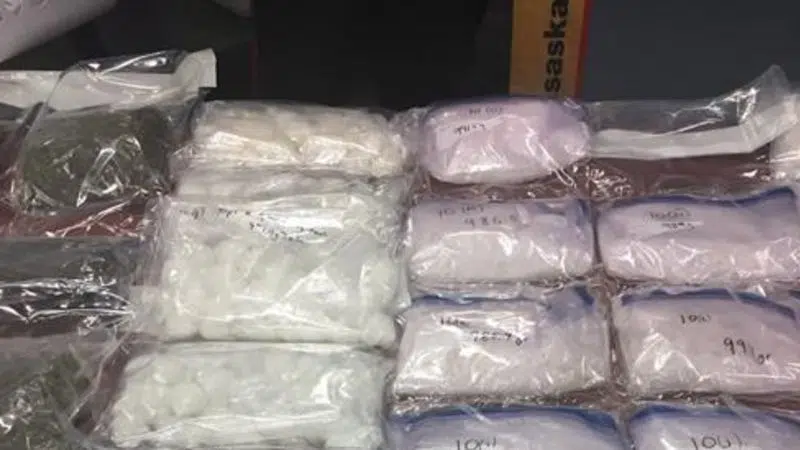

The committee made the recommendation, among others, in report produced after committee members travelled across Canada to witness the impacts of methamphetamine use and its rapid increase in some communities.

Many witnesses who appeared before the committee called for the federal government to work with provinces, territories, municipalities, Indigenous communities and law-enforcement agencies to decriminalize simple possession of small quantities of illicit substances, the report says.

It also says the committee heard during its informal meetings across the country that even some health-care providers have negative attitudes toward people with substance-use problems.