Man accused of killing ailing wife wasn’t suffering from major depression: expert

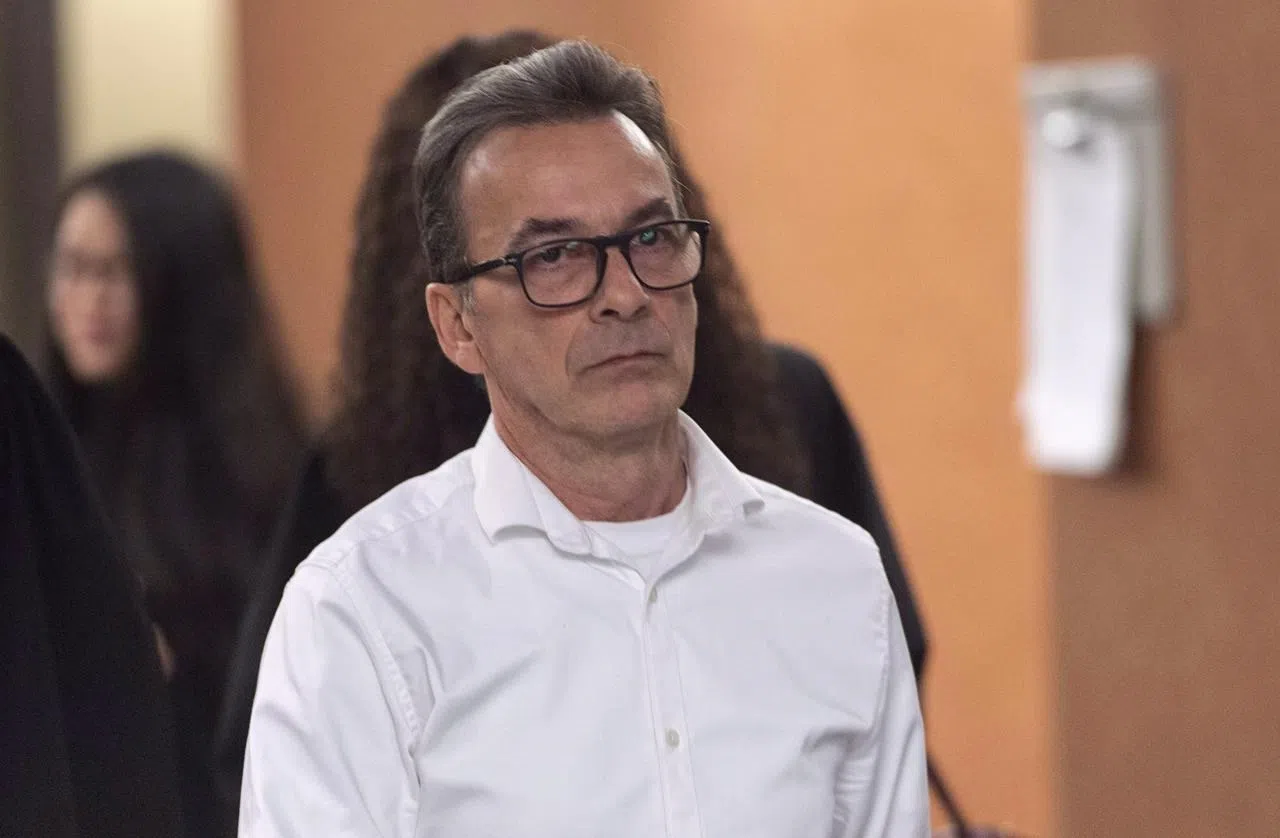

MONTREAL — A Crown expert cast doubt Monday on a Montreal man’s defence that he was suffering from depression that hindered his decision-making when he killed his severely ill wife nearly two years ago.

Dr. Gilles Chamberland is the final witness to take the stand at the second-degree murder trial of Michel Cadotte, accused of killing his wife, Joceylne Lizotte.

Testifying for the Crown, Chamberland told jurors Monday that Cadotte, 57, showed no evidence of major depression at the time of the killing.

Chamberland, who met with Cadotte last month, pointed to another factor behind the killing: heavy alcohol consumption the weekend before the slaying, which contributed to a secondary mood disorder — but not a major depression.