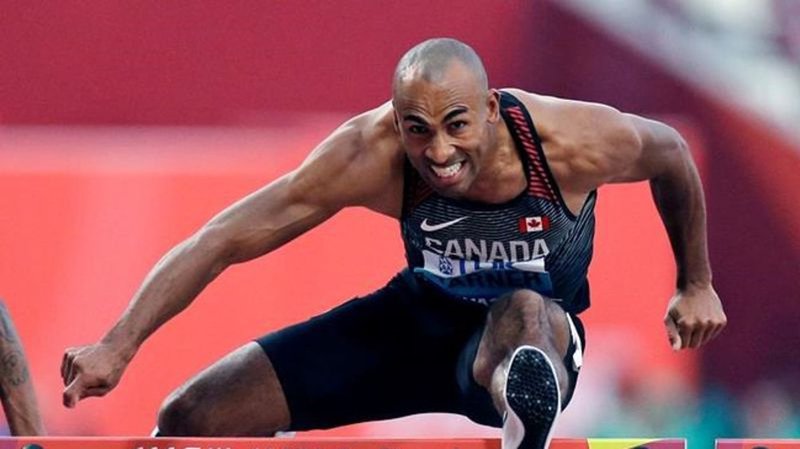

Damian Warner and Co., built a multi-events training facility in old London arena

Damian Warner’s training base is a 66-year-old unheated hockey arena that the City of London flagged for potential demolition more than a decade ago.

But it’s come to feel like home to the Canadian decathlon star in this bizarre Olympic year.

When COVID-19 forced Warner out of the University of Western and prevented him from crossing the border for warm-weather training in the U.S., Warner’s coach Gar Leyshon — with the help of “about 100 people” — built a multi-events facility in the spartan Farquharson Arena.

“Picture a really cold ice rink. And then take out the ice. That’s where we are,” Warner laughed.