B.C. advocates say relaxed drug offence penalties not enough amid deadly supply

VANCOUVER — Federal government proposals to relax penalties for personal drug possession are a positive step forward for Vancouver’s former drug czar, but they’re too small to address skyrocketing overdose deaths.

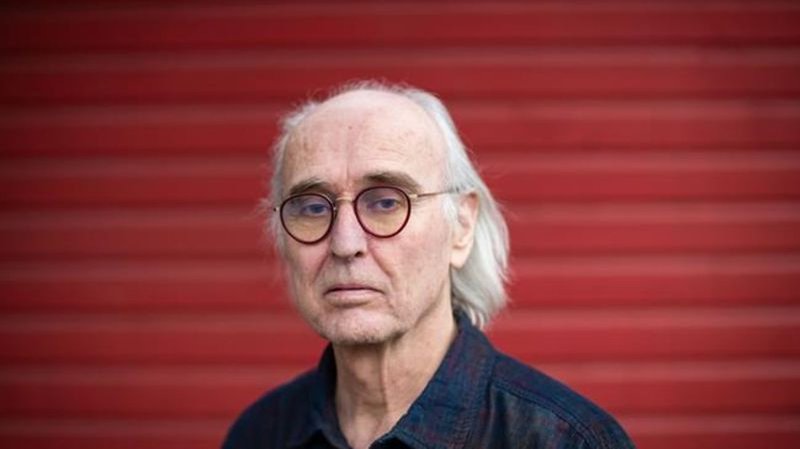

Donald MacPherson, director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition at Simon Fraser University, introduced the city’s drug strategy in the 1990s and the same principles guide the federal approach.

Today, he says that strategy isn’t enough and governments also need to adopt policy that matches the scale of the emergency.

“Our policy framework has created a monster, really, which is a drug market laced with illegal fentanyl and its analogues,” MacPherson said in an interview.