Gaining trust: History of Indigenous experiments [poses challenge in COVID health

WINNIPEG — Some leaders and health professionals say they are facing a challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic of persuading Indigenous people to trust a health system that has a history of experimenting on them.

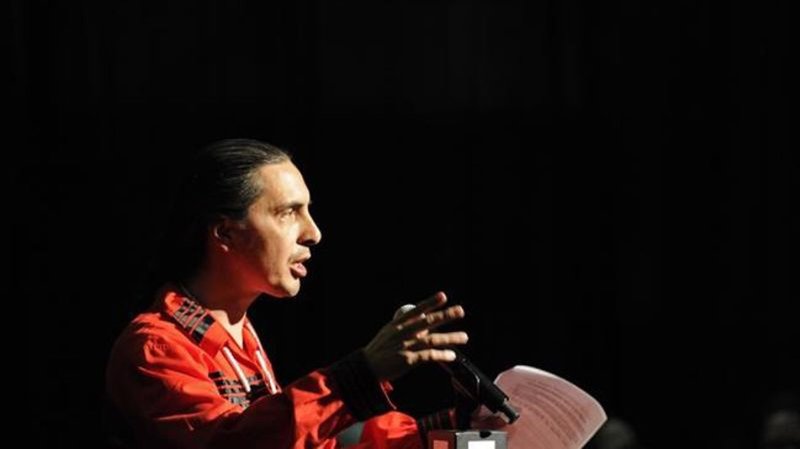

“There have been some deceitful and terrible things that have been done to our communities historically,” said Arlen Dumas, the Assembly of Manitoba Chief’s grand chief.

Dumas looked directly into the camera of his computer during the First Nations COVID-19 Pandemic Response Co-ordination Team’s last online update on Friday. He reassured those listening that Indigenous leaders would not allow horrific experiments of the past to be repeated.

“As far as I’m involved, things of that sort are never going to happen.”