Prison service trying to better understand the needs of black offenders

OTTAWA — Canada’s prison service is working to better understand the needs of black offenders, a community that is second only to Indigenous people when it comes to overrepresentation in federal custody

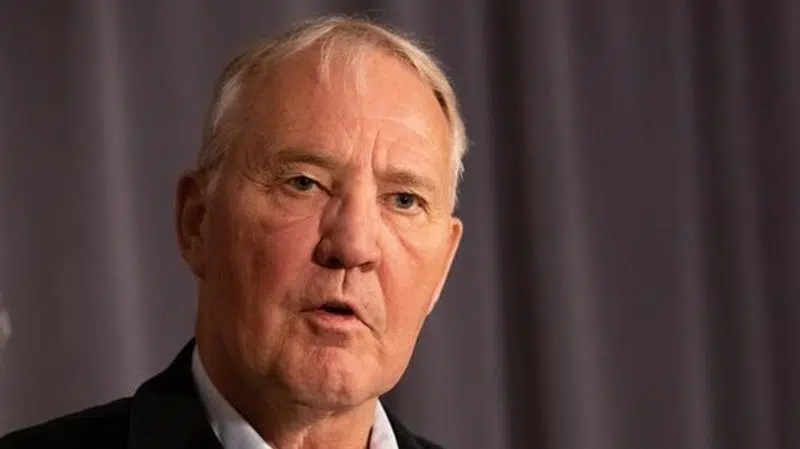

The Correctional Service of Canada has begun to study the black inmate population more closely and track the associated data, says a newly released briefing note, prepared for Public Safety Minister Bill Blair.

“Research is being conducted on the size, growth, geographic distribution, country of origin, as well as the language profile of the population.”

The effort comes seven years after a study by the federal prison ombudsman found black inmates commonly reported discrimination and stereotyping as gang members while in custody.