In Quebec, there’s no embarrassment in being called a nationalist

MONTREAL — Buying a new bathtub or kitchen sink isn’t a usually a political decision, but Quebec Premier Francois Legault tried to make it one this year with a subtle call in October to avoid a hardware company that moved jobs outside the province.

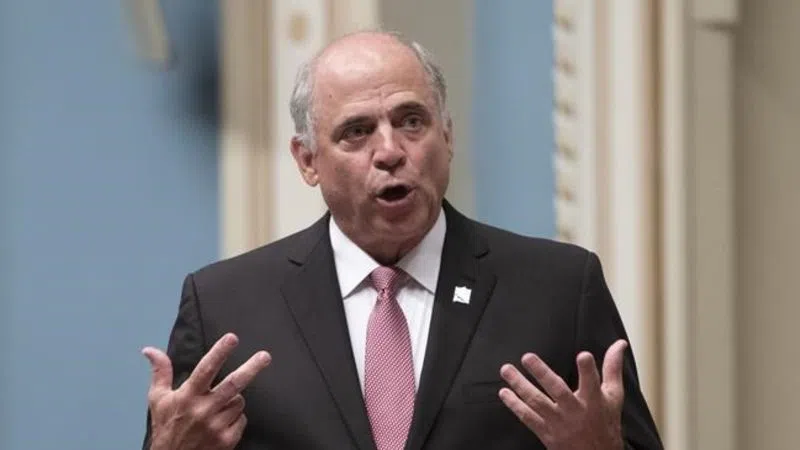

A month later, his economy minister, Pierre Fitzgibbon, publicly pressured the Desjardins Group bank to reconsider a decision against helping to finance a government-supported project to save six struggling regional newspapers. Desjardins changed its mind and is now a tentative partner.

In 2019, nationalism — whether harnessed to support homegrown businesses or to affirm the province’s distinct identity — was a winning political theme. It boosted the popularity of Legault’s Coalition Avenir Quebec government, which this year banned religious symbols for certain public sector workers and reduced immigration. And it helped revive the moribund Bloc Quebecois, propelling the party to its best federal election result since 2008.

Elsewhere, nationalism has taken on a negative connotation, associated in the United States with the “America First” rhetoric of President Donald Trump and in Europe with a rise of far-right governments and political parties calling for limits on immigration.