130-years later, historian recounts ‘devastating’ Nanaimo mine explosion

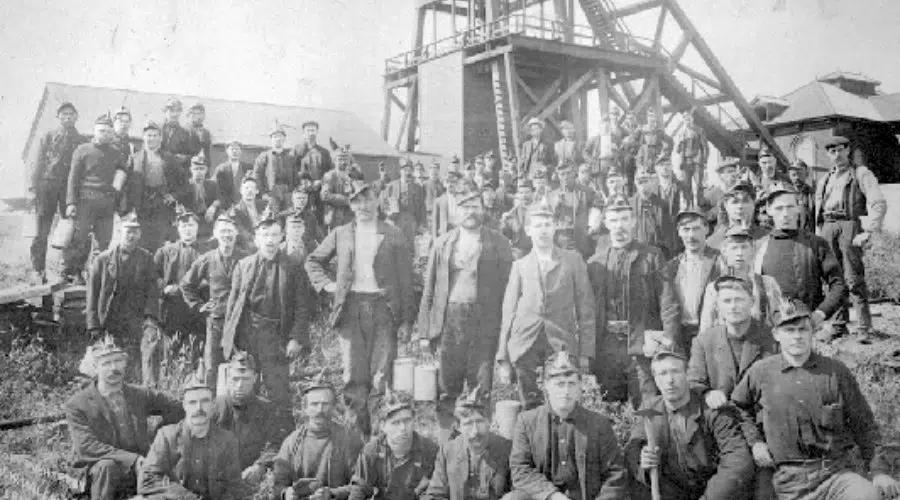

NANAIMO — The 130th anniversary of a pair of devastating explosions that killed 148 men working in a Nanaimo coal mine is raising memories of the vibrant and extremely dangerous industry.

The No. 1 Esplanade Mine, near the current cruise ship terminal, exploded after gas or dust was ignited on May 3, 1887.

The tragedy was the second worst mining disaster in Canada’s history.

Vancouver Island coal historian and author T.W. Paterson told NanaimoNewsNOW the tragedy had a massive ripple-effect on Nanaimo, which he said was home to a little more than 2,000 people at that time.