Dr. Donald: why the U.S. president keeps touting an unproven COVID-19 treatment

WASHINGTON — Americans and Canadians alike are used to seeing gauzy, pastel-coloured pitches for medicines, therapies and treatments on cable television. They’re less accustomed to hearing them delivered live from the White House briefing room.

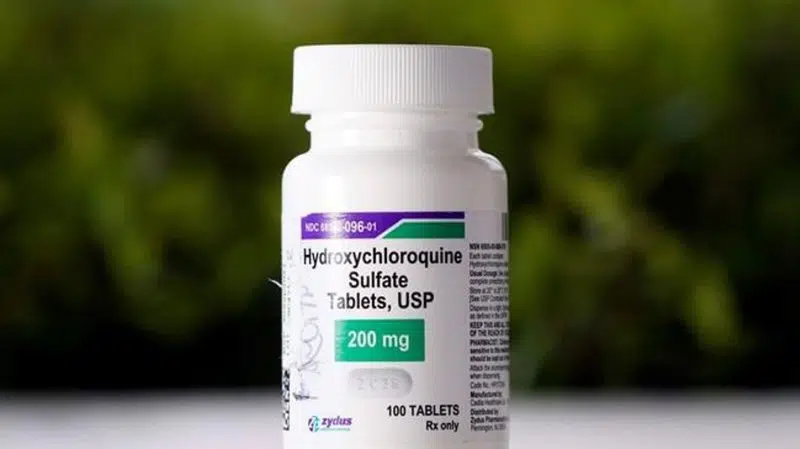

At times, Donald Trump’s nightly news conferences have come to resemble infomercials as the country’s pitchman-in-chief promotes hydroxychloroquine — an anti-malarial drug more commonly prescribed for diseases like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis that the president seems convinced carries promise for COVID-19 patients.

Trump said earlier this week that the U.S. has stockpiled 29 million hydroxychloroquine tablets — a strategy based on evidence that doctors, health care professionals, governors and infectious-disease experts across the country have described as inconclusive at best and downright dangerous at worst.

“What do I know? I’m not a doctor. But I have common sense,” the president said. “What do you have to lose?”