Canadians gleaned naval intelligence from Russian defector, newly released files show

OTTAWA — The young Russian seaman who turned up exhausted and bleeding on the British Columbia shore struck a Canadian intelligence official as well mannered, sincere and athletic, built like Tarzan of the movies.

Less than two years later, defector Sergei Kourdakov would die in a California motel room — apparently by accidentally shooting himself — after joining an evangelical Christian group dedicated to smuggling Bibles behind the Iron Curtain.

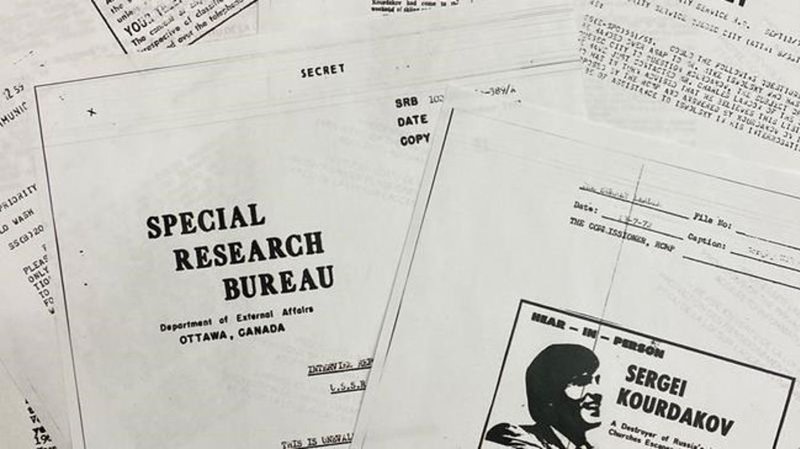

Newly released archival records of the RCMP Security Service shed fresh light on Kourdakov’s tragic odyssey, which made international headlines in the early 1970s. The classified memos, messages and reports also detail RCMP efforts to glean valuable intelligence from the unexpected visitor.

“He fully appreciated our interest in him and his information, and expressed a sincere desire to co-operate to the best of his ability,” reads one memo.