Media fight for details of Nova Scotia man’s wrongful murder conviction

HALIFAX — A court battle is set to unfold Tuesday over the release of key evidence explaining what led to the wrongful murder conviction of a Nova Scotia man who spent almost 17 years in jail.

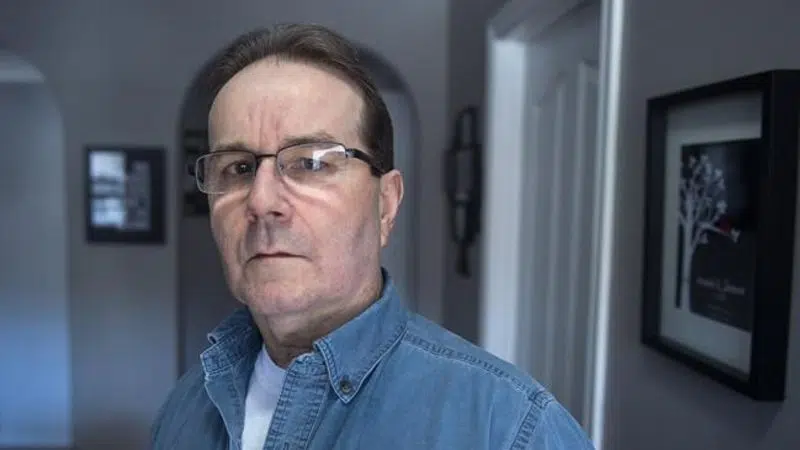

The Canadian Press, CBC and the Halifax Examiner will ask a judge for access to federal documents with details of how 63-year-old Glen Assoun was improperly convicted of second-degree murder on Sept. 17, 1999.

It’s a case where Canada’s minister of justice has already declared there was “reliable and relevant evidence” that wasn’t disclosed during criminal proceedings that Assoun has said ruined his life.

On March 1, after a two-decade struggle by Assoun to overturn his conviction, Nova Scotia Supreme Court Justice James Chipman found him innocent in the 1995 knifing death of 28-year-old Brenda Way.